Legal Corner

- Guy Lavergne

Two Years Into The Gun Ban: Where Do We Stand?

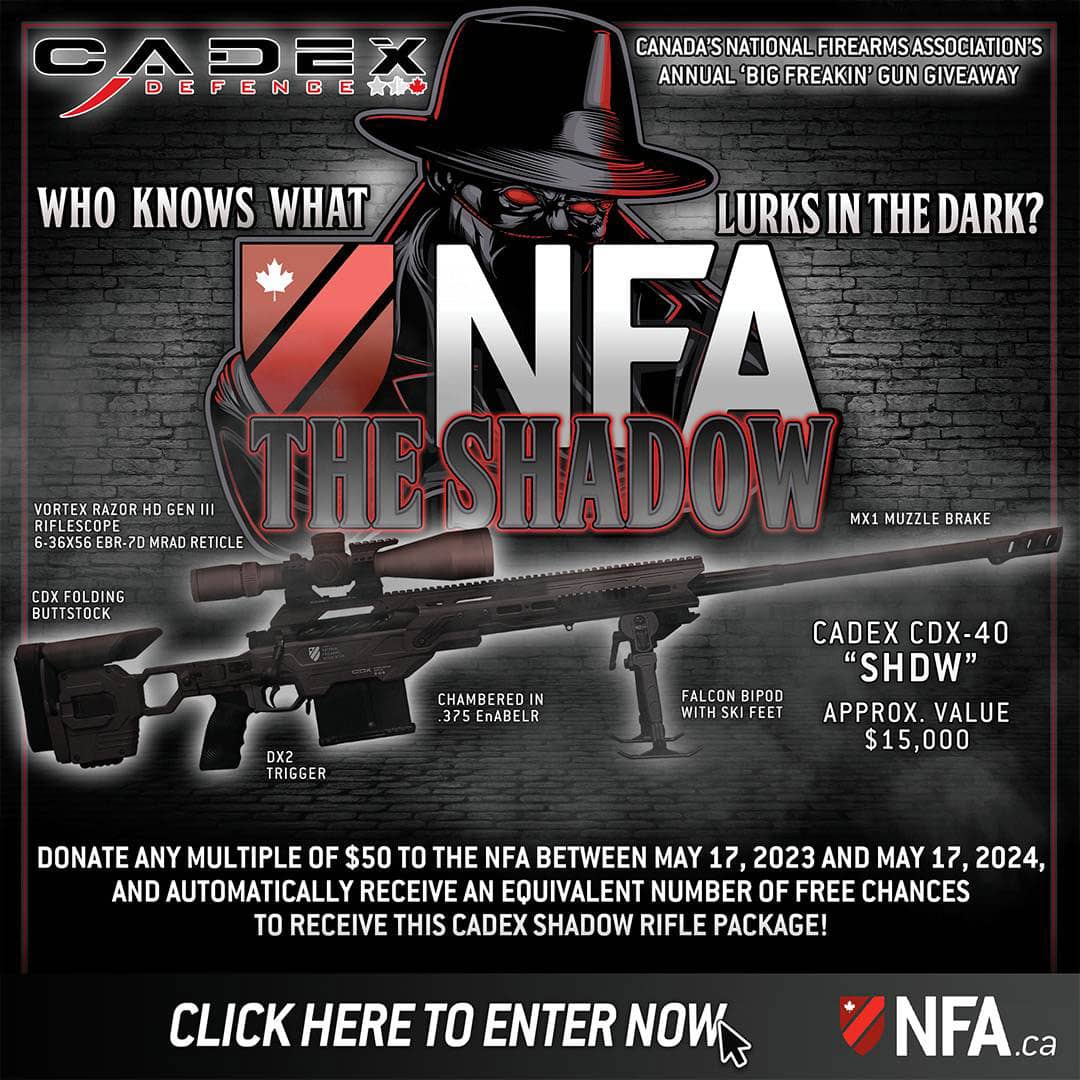

On May 1, 2020, the Canadian federal government implemented a wholesale prohibition of over 1,500 models of hunting and sporting rifles, calling them “military-type assault rifles.” Simultaneously, the government also banned firearms with a bore diameter of 20 millimetres or greater, as well as firearms that fire projectiles that carry more than 10,000 joules of kinetic energy at the muzzle (e.g., 375 Cheytac, 50 BMG).

The Timing Of The Ban

The ban had immediate effect. There was no buffer period or prior announcement that a change was to be effective on that date.

In truth, there had been advance warning, but nothing specific. For years, the Liberals had in their electoral platform a promise that they “would take the assault rifles off the streets.” Only they knew what that meant, since the 1,500 firearm models in question are not assault rifles, and none of them were out on the streets.

There was also an expectation that any ban would entail grandfathering, especially since provisions to that effect had recently been added to the Firearms Act (i.e., Paragraph 12(9), etc.) through Bill C-71. In that respect, the government chose to ignore the legislation that parliament had passed (at their own initiative) mere months beforehand.

The gun ban was announced and took effect days after the Nova Scotia killing rampage, in which Gabriel Wortman killed 22 people over two days. The timing of the ban was likely meant to be perceived by the public and media as the federal government’s response to that killing spree. Of course, Wortman had acquired all his firearms illegally (i.e., through illegal transfers, smuggling and theft), and most of them had also been smuggled into Canada. The government is oblivious to the fact that its “response,” had it been implemented earlier, would not have prevented any of Wortman’s actions. I will let you be the judge of whether that “response” was meant to take the public and the media’s attention away from the BSA and RCMP’s own failures that contributed to the tragedy.

The Means Used

The gun ban was implemented through an Order In Council (OIC). An OIC is an instrument that reflects a decision of the federal cabinet. To be valid, it must be based upon a statutory power, or the common law. In the instant case, the government’s position is that it could do so pursuant to its power to prescribe (i.e., regulate) certain firearms as being unfit for sporting or hunting usage in Canada.

The Obvious Lack Of Preparation

The OIC contemplates a so-called buy-back program. “Forced confiscation” or “expropriation” would have been better terms, since the government never owned the newly banned firearms in the first place. In any event, it is contemplated that the banned firearms will have to be turned over to the government and that some financial compensation will be paid to the owners thereof.

Two years after the OIC, no legislation relating to that expropriation/compensation program has been filed before parliament, much less enacted. It is still unknown whether compensation would be at fair market value or on a different basis.

To my knowledge, the only concrete steps taken thus far have been a call for tenders to devise/manage the compensation program, as well as

a solicitation of firearms dealers to volunteer to collect and/or deactivate the banned firearms. Unsurprisingly, there have been very few, if any, volunteers for the latter task.

The Legal Challenges

Within weeks of the enactment of the ban, multiple parties filed legal challenges of the OIC before the Federal Court of Canada.

The first parties to file a challenge were Cassandra Parker and her company, KKS Tactical Supplies (federal court case T-569-20). That challenge is sponsored by the NFA. The NFA itself filed a motion for leave to intervene as a party in that challenge. The court will adjudicate that motion and other similar motions by would-be interveners in the fall of 2022.

A total of five such challenges are currently pending before the federal court, and they will all be heard together towards the end of this year or early in 2023.

The Amnesty Period

Since the ban was enacted with immediate effect, the government had no choice but to also enact a general amnesty in favour of the individuals and businesses that were legally in possession of the banned firearms at the time of enactment. This was also necessary because the OIC, while prohibiting use and transfer, specifically provided that current owners were to retain possession of their newly prohibited firearms until the buy-back scheme is implemented. The government could not, on the one hand, allow owners to retain their firearms, but on the other hand make them liable to criminal prosecution for doing so.

The original amnesty period had a duration of two years. In the fall of 2021, it became increasingly clear that the two-year amnesty period would not suffice. Indeed, the government had not followed through on its plan to implement a buy-back program and there was little to no chance that it was going to be implemented before the expiry of the two-year amnesty period.

At a case management conference between the attorneys for the litigants, the federal court’s associate chief justice took the initiative of booking a temporary injunction hearing for April 11, 2022, even though no party had yet made a motion for such relief, as it had become obvious that without a court order staying some aspects of the OIC, a large number of Canadian gun owners were at risk of becoming liable to criminal prosecution upon expiry of the then current two-year amnesty period.

That April 11 hearing never took place. Instead of getting a legal slap in the face from the federal court , which looked like a near certainty, the government chose to extend the amnesty period for an extra 18 months, pretexting that gun owners needed additional time to comply with the ban. That is of course a fallacy, meant to hide the government’s own shortcomings and lack of preparedness.

Given the current pace of things, a further extension of the amnesty period is far from impossible.

Now What?

Seeing that the current Liberal government has yet to even file proposed legislation to support a buy-back program, it seems likely that the federal court will hear and decide upon the validity of the OIC before any such legislation comes into effect.

A decision favourable to gun owners would have immediate effect but could be stayed by the Federal Court of Appeal.

The government could also be waiting for a court decision on purpose, to remedy any issues that make the OIC invalid through legislation. Indeed, if the federal court finds the OIC to be invalid, parliament could then remedy the underlying invalidity through statute, if the reason for the invalidity is not a constitutional one.

In other words, the only certainty at this point is that the future is uncertain.

Guy Lavergne, Attorney at Law